How to Hack a Phone, Cocaine Style

“That man needs to sleep. At all costs, brother. That’s what needs to happen, brother” Ridouan Taghi wrote in a text message.

“He knows we’ll let everyone sleep on him if he has mentioned my name,” he says in another.

“Sleep” had prompted an alert, as did “liquidate” and “crack” — all code words for murder.

In Episode 1, we heard the texts from the criminal underworld, those which were obtained from massive police hacks. Here’s some more details on how we have those texts today:

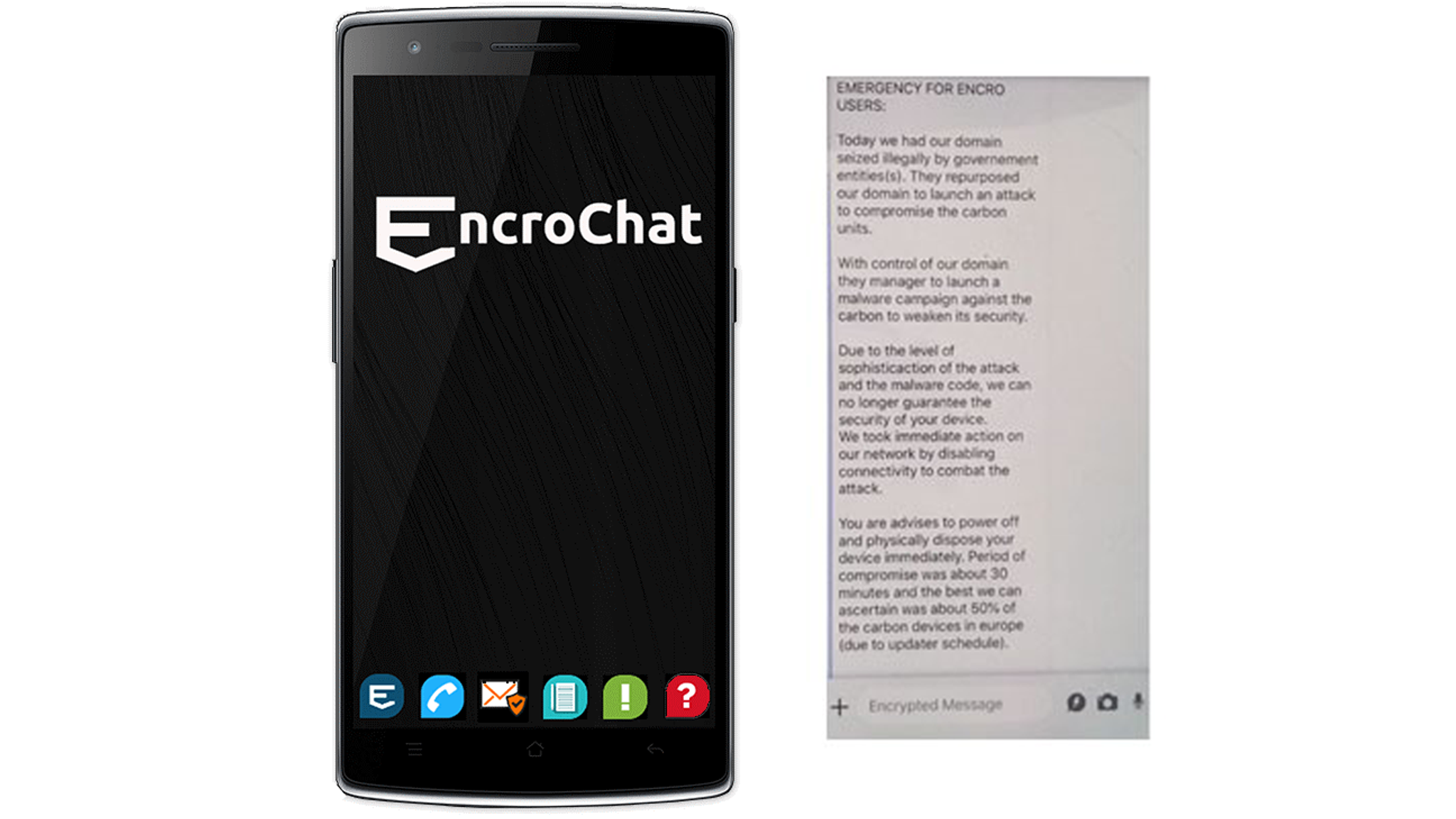

First the criminal’s choice phone network was EncroChat.

The company, founded in 2016, was one of the largest providers of encrypted digital communication. They provided modified mobile handsets that had their microphones, cameras and GPS systems removed. The devices then have a special operating system and messaging software installed on them, which would send and receive encrypted messages.

User hotspots were particularly present in source and destination countries for cocaine and cannabis trade, as well as in money laundering centres.

EncroChat had previously claimed that it housed its servers in secure locations “offshore.” But they were actually in a data center in Roubaix, a city in northern France. The French National Gendarmerie realized that all EncroChat communications routed through Roubaix and started investigating in 2019, alongside the Dutch.

In early 2020, they revealed they had compromised the EncroChat network. They beat the encrypted system by planting malware which syphoned off more than 100 million messages. Eventually, they also figured out how to read messages in real time.

“It was as if we were sitting at the table where criminals were chatting,” Jannine van den Berg, chief constable of the Dutch police, said at the time.

Jan Op Gen Oorth at Europol told us that the hack illustrated just how big the world of organized crime was. “It's bigger than we thought. It's more international than we thought,” he explained. “They're better connected than we thought. They're moving more cocaine, more drugs than thought, more languages involved.”

A number of high-profile arrests and drug busts followed — in the Netherlands police arrested 100 people and found 19 meth labs. EncroChat was shut down in July.

With the downfall of EncroChat, many users switched to Sky E.C.C.

The company was founded in 2008 and by 2020, had approximately 70,000 active users. Nearly a quarter of them were clustered around Europe’s busiest seaports: Rotterdam and Antwerp.

But it was cracked by Belgian and Dutch authorities. In March 2021 they announced the attack, which caused widespread panic for users around the world.

Similar to the process of hacking EncroChat, police first intercepted and stored encrypted communications from the Sky ECC network, while experts worked out how to decrypt them. In the second phase, police were able to read live data sent across the network. Even weirder, Sky’s servers were also in the French city of Roubaix.

The Belgian police said the arrested over 1000 people after the hack. Earlier this month European police also arrested three people in Belgrade described as "the biggest" drug lords in the Balkans.

“Most of the criminals know that one day they'll get a knock on their door and it's their time to go to the prison,” Belgian journalist Joris van der Aa told Gateway. “There's so much evidence that the police have to work one after another, after another.”

While police insist these services were legally hacked, there has been a growing number of questions surrounding the hackings the invasion of privacy. At the end of last year, a case in Germany was sent to Europe’s highest court, regarding whether the obtained messages broke data-sharing laws across Europe. If it wins, the case could potentially undermine the convictions of thousands around Europe.

Listen to Gateway for more on Taghi…